Executive Summary: Snakes are often killed at sight, even if not venomous. Social and cultural connotations, some more negative than others, and fear of snakebite shape our attitudes towards snakes and lead to human snake conflict. But snakes play an important role in our ecosystem and provides us economic and therapeutic benefits. It is high time we now start valuing the importance of snakes in biodiversity to make our societies healthier.

Snakes, as serpent deities are revered in various cultures - as a symbol of fertility, rebirth, afterlife, medicine, healing and prosperity.[1-4] Paradoxically, in communities, they are also considered as a threat to life and livelihood. Ophidiophobia, the fear of the snakes, is one of the most common phobias of animals (affecting 2-3% human population).[5, 6] Snakes are often killed on sight, for fear of snakebite.

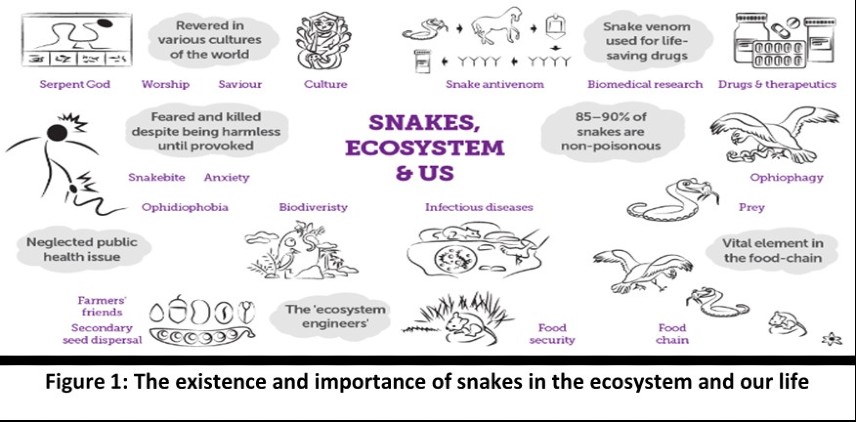

Globally, up to 138,000 people die due to snakebite every year with nearly 2.7 million people suffering serious injuries and permanent disabilities.[7] However, about 85-90% of snakes species worldwide are non-venomous.[8] Most snakes are not aggressive in nature, and often bite in defence, or when threatened or provoked.[9] Killing snakes for fear of snakebites is problematic – as decreased snake population is detrimental not only for the environment but also for humans. Snakes serve critical role as predators, as preys, as ecosystem engineers, and provide economic and therapeutic benefits to humans (Figure 1).

Snakes as predators, feed on frogs, insects, rats, mice, and other rodents, helping to keep prey population under control. Snakes are also eaten by other species - thus playing a key role in the food-chain as prey. Skunks, mongooses, wild boars, hawks, snake eagles, falcons, and even some snake-species are Ophiophagus, i.e. species who feed on snakes as their primary diet.[10-12] The king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), eastern king snake (Lampropeltis getula), black-headed python (Aspidites melanocephalus), eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon couperi) are some ophiophagus snakes.[13-15] Declining snake population not only effects ophiophagus species, but has effects across many trophic levels. A disrupted ecosystem in the context of climate change, an increased probability of natural disasters has the potential to cause massive loss of life and livelihood.[16-18] The declining population of snakes has been documented globally.[19]

Snakes as ‘ecosystem-engineers’ facilitate ‘secondary seed dispersal’, thus contributing to reproduction of plants.[20-22] When snakes swallow rodents (who consume seeds), the seeds are expelled through excretion into the environment in an intact manner. As snakes have larger home ranges than rodents, seeds tend to disperse at greater distances from the parent plant.[23] This mechanism supports growth and survival of plant species without struggling for common resources of light, water, and soil nutrients and hence essential for biodiversity and ecological restoration.[24]

Snakes also play a role in disease prevention and provide benefits to agricultural communities. Rodents are carriers of many zoonotic diseases (like Lyme disease, leptospirosis, leishmaniasis, hantavirus) which affects humans, dogs, cattle, sheep, and other domestic animals.[25-28]. A sudden increase in rodent population might lead to zoonotic diseases outbreaks.[29]. Increase in population of rodents leads to loss of crops.[30] By eating rodents, snakes keep the population of rodents under control, thus preventing zoonotic disease transmission, and contributing to food security.[31] Estimates suggest that nearly 200 million people can be fed by food grains that are destroyed by rodents every year.[30] Offering natural, environmental-friendly, and free service to mitigate against rodents, snakes are truly “farmer’s friends”.[32]

Snakes are also a source of many medicines. The only proven and effective therapy for snakebite - the snake-anti venom, is also derived from snake venoms.[33] Snake venom is injected into horses and sheep. The animals’ plasma with antibodies against the venom is collected and purified to produce the life-saving, snake anti-venom. [34] Snake venom has therapeutic value beyond anti-venom production. Many drugs derived from snake venoms are used in clinical practice (Table 1). [35-38] However, the therapeutic potential of snake venoms remains unexplored. Venom researchers continue to discover and investigate many more compounds.

With the effects of climate change now evident, it is time now to start valuing the importance of biodiversity in making our societies healthier. Let’s save the snakes!

Table 1: Snake venom derived drugs which are approved for clinical use [35-39]

| Snake species | Name of Drug | Disease / Condition |

|---|

| Jararaca pit viper snake(Bothrops jararaca) | Captopril Enalapril | Hypertension; Cardiac failure |

| Saw-scaled viper(Echis carinatus) | Tirofiban | Acute coronary syndrome; Unstable angina |

| Brazilian lancehead snake(Bothrops moojeni) | Batroxobin | Autologous fibrin sealant in surgery |

| Chinese cobra (Naja naja atra) | Cobratide | Chronic arthralgia; sciatica; neuropathic headache |

| South-eastern Pygmy Rattlesnake(Sistrurus miliarius barbourin) | Eptifibatide | Acute coronary syndrome, percutaneous coronary intervention |

Author contributions

Conceptualisation - SB and DB; Writing original draft – DB; Writing- review and editing – SB, DB; Guarantor – SB and DB

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge feedback received from Maarinke van der Meulen and Jagnoor Jagnoor from The George Institute for Global Health.

Publication Note

The working paper is a part of a deep-thinking report on snakebite.

Suggested Citation

Beri D, Bhaumik S. - Snakes, the ecosystem, and us: it’s time we change. The George Institute of Global Health. July 2021. Available online at www.georgeinstitute.org. The article is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

References

- Antoniou, S.A., et al., The rod and the serpent: history's ultimate healing symbol. World J Surg, 2011. 35(1): p. 217-21.

- Behjati-Ardakani, Z., et al., An Evaluation of the Historical Importance of Fertility and Its Reflection in Ancient Mythology. Journal of reproduction & infertility, 2016. 17(1): p. 2-9.

- Bird, S.R., "Australian Aborigines". In William M. Clements (ed.), in The Greenwood Encyclopedia of World Folklore and Folklife. 2006 Greenwood Press: Westport, CT. p. 292–299.

- Mundkur, B., The Roots of Ophidian Symbolism. Journal of the society for Psychological Anthropology, 1978. 6(3): p. 125-158.

- Ceríaco, L.M., Human attitudes towards herpetofauna: the influence of folklore and negative values on the conservation of amphibians and reptiles in Portugal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed, 2012. 8(8).

- Polák J, et al., Faster detection of snake and spider phobia: revisited. Heliyon, 2020. 6(5): p. e03968.

- World Health Organization, Factsheet: Snakebite envenoming. 2021: p. Cited 15 June 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/snakebite-envenoming.

- Meyers, S.E. and P. Tadi, Snake Toxicity. [Updated 2021 Jan 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2021: p. Cited May 27, 2021. Available from: Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557565/.

- Coelho, C.M., et al., Are Humans Prepared to Detect, Fear, and Avoid Snakes? The Mismatch Between Laboratory and Ecological Evidence. Frontiers in psychology, 2019. 10: p. 2094-2094.

- Animal Hype, What Animals Eat Snakes? (A List Of Snake Predators). 2021(Cited May 31, 2021. Available from: https://animalhype.com/facts/what-animals-eat-snakes/).

- Dykstra, J., What animals eat snakes? Grunge 2019. Cited May 31, 2021. Available from: https://www.grunge.com/161123/what-animals-eat-snakes/.

- Zainal Abidin, S.A., et al., Malaysian Cobra Venom: A Potential Source of Anti-Cancer Therapeutic Agents. Toxins, 2019. 11(2): p. 75.

- Jackson, K., N.J. Kley, and E.L. Brainerd, How snakes eat snakes: the biomechanical challenges of ophiophagy for the California kingsnake, Lampropeltis getula californiae (Serpentes: Colubridae). Zoology (Jena), 2004. 107(3): p. 191-200.

- McCracken, J., Aspidites melanocephalus - Black-headed Python. Animal Diversity Web, 2020 (Cited May 31, 2021. Available from: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Aspidites_melanocephalus/).

- Oddly cute pets, What Snake Eats Other Snakes? 2019 (Cited May 31, 2021. Available from: https://oddlycutepets.com/what-snake-eats-other-snakes/).

- World Health Organization, Factsheet: Biodiversity and Health. 2015(Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/biodiversity-and-health).

- Pyšek, P., et al., Scientists' warning on invasive alien species. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc, 2020. 95(6): p. 1511-1534.

- Adebayo, O., Loss of Biodiversity: The Burgeoning Threat to Human Health. Annals of Ibadan postgraduate medicine, 2019. 17(1): p. 1-3.

- Reading, C.J., et al., Are snake populations in widespread decline? Biology letters, 2010. 6(6): p. 777-780.

- Hämäläinen, A., et al., The ecological significance of secondary seed dispersal by carnivores. 2017. 8(2): p. e01685.

- Glaser, L.B., Snakes act as 'ecosystem engineers' in seed dispersal. Cornell Chronicle, 2018 (Cited May 21, 2021. Available from: https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2018/02/snakes-act-ecosystem-engineers-seed-dispersal ).

- Sunyer, P., et al., The ecology of seed dispersal by small rodents: a role for predator and conspecific scents. 2013. 27(6): p. 1313-1321.

- Hasik, A., Snakes spreading seeds. Ecology for the masses, 2018(Cited May 31, 2021. Available from: https://ecologyforthemasses.com/2018/08/16/snakes-spreading-seeds/).

- Ruxton, G.D. and H.M. Schaefer, The conservation physiology of seed dispersal. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 2012. 367(1596): p. 1708-1718.

- Moola, S., et al., Leptospirosis prevalence and risk factors in India: Evidence gap maps. 0(0): p. 00494755211005203.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Rodents. 2010: p. Accessed 03 April 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/rodents/index.html.

- Himsworth, C.G., et al., Rats, cities, people, and pathogens: a systematic review and narrative synthesis of literature regarding the ecology of rat-associated zoonoses in urban centers. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 2013. 13(6): p. 349-59.

- Rabiee, M.H., et al., Rodent-borne diseases and their public health importance in Iran. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 2018. 12(4): p. e0006256-e0006256.

- Miller, J., A World Without Snakes. In Forestry and Wildlife. 2020 (Cited June 02, 2021. Available from: https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/forestry-wildlife/a-world-without-snakes/).

- Singleton, G.R., et al., Impacts of rodent outbreaks on food security in Asia. Wildlife Research, 2010. 37(5): p. 355-359.

- Jowit, J. and A. Searle, Snake numbers ‘in decline'. The Hindu, 2010 (Cited June 02, 2021. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/Snake-numbers-lsquoin-decline/article16242431.ece).

- Save The Snakes, Why Snakes? 2021(Cited May 31, 2021. Available from: https://savethesnakes.org/s/why-snakes/).

- Ferraz, C.R., et al., Multifunctional Toxins in Snake Venoms and Therapeutic Implications: From Pain to Hemorrhage and Necrosis. 2019. 7(218).

- World Health Organization, Snakebite envenoming. 2021 (Cited May 31, 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/snakebites/antivenoms/en/).

- Bansal AB, Sattar Y, and Jamil RT, Eptifibatide. [Updated 2020 Nov 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2021: p. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541066/.

- Bordon, K.d.C.F., et al., From Animal Poisons and Venoms to Medicines: Achievements, Challenges and Perspectives in Drug Discovery. 2020. 11(1132).

- Mohamed Abd El-Aziz, T., A. Garcia Soares, and J.D. Stockand, Snake Venoms in Drug Discovery: Valuable Therapeutic Tools for Life Saving. Toxins, 2019. 11(10): p. 564.

- Péterfi, O., et al., Hypotensive Snake Venom Components-A Mini-Review. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 2019. 24(15): p. 2778.

- Takacs, Z. and S. Nathan, Animal Venoms in Medicine, in Encyclopedia of Toxicology (Third Edition), P. Wexler, Editor. 2014, Academic Press: Oxford. p. 252-259.