Tracking laws that govern the determinants of health: some reflections on why and how

Blog by Kent Buse & Devaki Nambiar

To mark World Health Day, are calling for a ‘World Wellbeing Watch.’ Such an initiative would track the progress among countries on the legal frameworks addressing the social determinants of health (SDoH). In making the case, we observe that initiatives exist to track a large number of health outcomes in an impressively detailed way (the most prominent of which is the Global Burden of Disease), but that efforts to track government legislation pertaining to the drivers of ill health or well-being tend to be more ad hoc and issue-specific. We have published an editorial in the British Medical Journal making the case for such an initiative; in this blog we explore how such a task might be approached. We do so with the aim of starting a series of conversations with those who, like us, want to see greater action on such legislative frameworks.

Social and commercial determinants: a neglected area of public health practice

The opportunity to live a healthy life is a basic human right. But any reasonable chance of people realising that right by achieving health-related targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will be a chimera if there are not hugely stepped-up efforts on the social determinants. Report after report, reckoning after reckoning, has concluded that lack of action on the conditions in which we are born, live, grow, work, and age has compromised health and well-being, with COVID-19 serving as a stark reminder that the greatest loss of life, the severest economic and social impacts have been endured by those already multiple overlapping disadvantages. This is a product of both our neglect of and profiteering from this disadvantage and our lack of solidarity with each other.

Laws matter

The important role of global public health law has been made evident in health realms as diverse as road safety, HIV, tobacco, air quality, food security, and environmental health. As these examples demonstrate, laws assign duty-bearers – actors with institutional responsibility for implementation – in this instance, to ensure that groups facing disadvantage receive entitlements, protections, and services. Laws also matter because they endure. Even as duty bearers change, fashions and trends morph, how we think and what we do, laws hold societies to certain fundamental – and justiciable – commitments and accountabilities.

Which laws matter?

Arguably, one of the many challenges facing the social determinants agenda, is its breadth. Where to start and how to prioritize? The terrain of economic, built and commercial determinants is vast and efforts are dispersed across many government ministries and departments. We’re thinking that a logical starting point for an effort to track legislation on these determinants, would be with the Sustainable Development Goals framework. Not only have the SDGs and their guiding principle of “leaving no one behind” been agreed by governments themselves, but the goals are described as mutually dependent. And as with the other goals, the health goal is dependent on progress on the targets of other goals, such as decent work, education, gender equality, equity, effective institutions and so on (that is, the social determinants).

Within the SDG framework, it might make sense to start with the most obvious SDGs and SDG targets that have clear relationships to and serve as key determinants of health. Then within each of these goal areas, one might seek evidence of the impact of good laws on relevant health outcomes. This could be a good way to start to identify the range of critical laws to track. Using this information, one could reach out to affected and interested communities to get their perspectives on good and bad laws that affect their ability to protect their health and the health of their families. One could also seek the views of experts and law-makers in specific issue areas to help identify laws which might be most relevant to improve people’s health and well-being. On the basis of those conversations one might select a range of priority laws to consider in a tracking exercise.

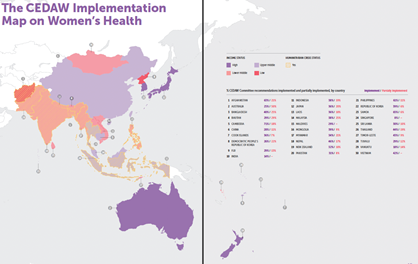

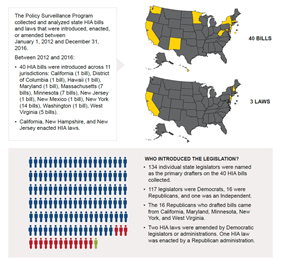

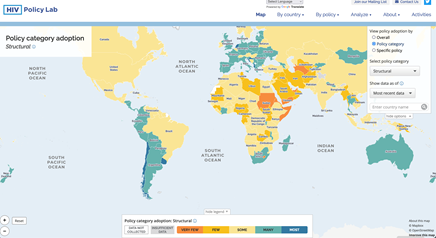

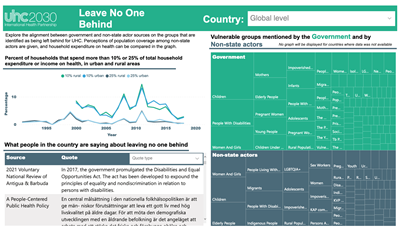

What we would then want to know is which organisations already collect information on whether or not governments adopt the relevant laws, and assess whether they are good or bad, whether they are implemented and whether they have provisions that would promote equity. While we at the George have done some work on this in relation to the Convention on Eliminating all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), there are analogous efforts, such as Temple University’s policy surveillance program, including the HIV Policy lab, as well as the UHC2030 Civil Society Engagement Mechanism’s State of the UHC Commitment, which features a progress review portal that innovatively integrates qualitative and quantitative information describing levels and processes of commitment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Policy & Legal Surveillance Dashboards – an Illustration

Source: Websites of CEDAW Implementation map, The LawAtlas Policy Surveillance Project, the HIV Policy Lab, State of the UHC Commitment.

Process matters

We see merit in a database that tracks and visualises whether and how governments are legislating to protect well-being across a range of public policy areas and have some ideas about how to build one. Initial conversations with colleagues in international organisations, governments and research have revealed a latent interest is such an effort. Yet, it is arguably the case that communities, workers, the unemployed, students, migrants, the economically disadvantaged, young people, consumers, climate activists, opposition parties - those people who have the greatest stakes - are in the best place to tell us what laws matter to them, and what an initiative has to look like and do for them to effectively use it to hold governments to account to legislate for health and well-being.

We are looking for ways to engage with a range of actors to fill the gap in accountability for good laws to protect and promote health and well-being. To start, we should be coming together to organise our demands to government. We need to figure out how we can make it harder, indeed impossible, to ignore what matters for health and well-being. We at the George Institute for Global Health are collaborating with the UHC2030 Civil Society Engagement Mechanism on a program of work to promote social participation for health – linking this work to upstream determinants and to legal entitlements will be one way in which evidence and knowledge meets advocacy and action.

Legal reform takes time, and the path to creating accountability mechanisms will also present many challenges: we may stumble – but we will do it together, and that will matter.